Two students, Doroteja Antić (communicology) and Aleksa Ćirić (journalism) from NoviSad University joined the Danube Dialogues team this year. Our latest bulletin, DD 2021, reports their conversations with artists, curators, selectors and friends of the Festival. For interviews with the artists Karolina Mudrinski, Antoni Rayzhekov, Dragan Vojvodić and Vladimir Kopicl, see below.

KAROLINA MUDRINSKI is an artist from Novi Sad making her debut at the Danube Dialogues this year. Her exhibition Novi Sad+ is based on her doctoral dissertation and the connection and interaction of 2D and 3D spaces. Karolina’s work can be described as ‘art explained by science’. Her own interpretation is that she views science not only as her field of interest but as the basis for her works.

DD: This is the first time you’ve taken part of the Danube Dialogues. How do you find working with the organizers, curators and artists? What’s your impression of the festival itself so far?

KM: That’s right. This is the first time I’ve taken part in the festival, and my exhibition is also the first of this year’s series, so I haven’t really been able to compare my work with the other artists. Nevertheless I’m looking forward to the rest of the event and to discussing the main topic with the others.

DD: Your work is mainly based on a combination of art and science. Is a sound grasp of mathematical principles crucial to the creative process?

KM: I believe that we can’t really understand the postulates of art without understanding mathematical postulates. Art provides space for various possibilities – everything can be presented, proved or defined. From my point of view, it all comes down to the study of art and science.

DD: How hard is it to combine the two?

KAROLINA: To me it came naturally. I find it very interesting, a constant source of inspiration, which is why I’ve been studying it for years. My knowledge of art makes me better able to present my scientific research.

DD: Like this, you bring the artist and science closer together. Do you think your work might also connect scientists to art, create a stronger bond between the two?

KM: This exhibition is part of my doctoral dissertation. While I was making it and writing my master’s thesis, I worked with multiple mathematicians, physicists and programmers. It helped me understand science on a much deeper level, and this was an important contribution to my work and in introducing science into art.

ANTONI RAYZHEKOV is a Bulgarian artist whose work was presented in the festival’s main exhibition: “Society and art in a forced reality”. This was an interactive map of the world with a switch for every country. The audience could then turn each of them on or off, changing the sound constantly emanating from the map. Antoni’s work as he views it, though inspired by the pandemic, also sheds light on crises that are less visible or consequences that are not immediately present or seen.

DD: Considering the fact that your work is mainly based on the pandemic, do you think that it may have divided artists around the world, or did it bring them even closer?

AR: The pandemic had certainly separated entire countries, economies, cultures and many other aspects of society – the question is „what did we learn from that?“. The pandemic showed us that listening is an important contribution to communication. If everyone talks and no one listens we get noise, a damage even bigger than the pandemic itself. That is exactly why we desperately need a communication platform, and in this case art plays that role. My work is a reflection of this metaphor – by switching the countries „on“ and „off“ you are shutting them out, you prevent them from communicating. In these circumstances, we must remember that each person’s responsibility is extremely important, and then we may put a stop on people constantly excluding each other so easily.

DD: Do you believe that art can be an escape from pandemic or a tool for gaining a better outlook on the entire situation and crisis that we’re all in?

AR: „What is art“ is a question that art itself imposes constantly. From one point of view, art reflects the hidden processes that may not be obvious at a first glimpse, such as fear or paranoia, and on the other hand it can highlight the processes that may seem irrelevant, but are actually essential. In the end, art is always there to open our eyes and help us see things more clearly.

DD: Do you believe that in the future „pandemic art“ will be viewed as a separate branch of art?

AR: It’s interesting to think about that and try to predict the course of the future. We already have numerous artworks that can be interpreted as a direct response to the pandemic, and I believe that one day it might become an independant chapter in art history.

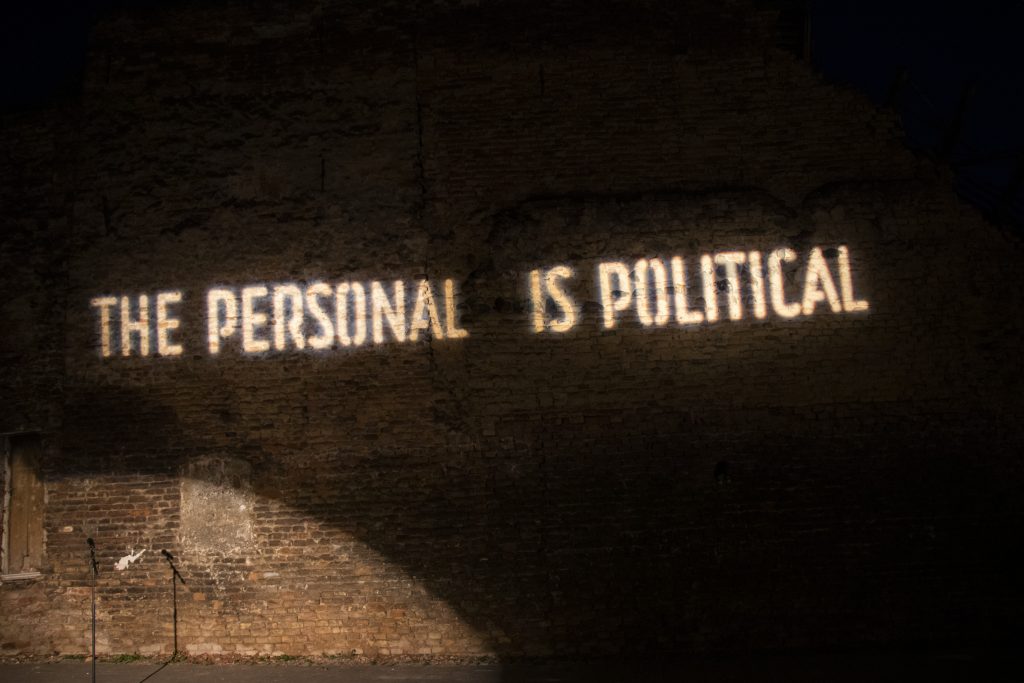

DRAGAN VOJVODIĆ is a Serbian artist who presented “The personal is Political”, a work which was a part of the “Novi Sad – Timisoara” dialogue. Dragan is mostly known to the public for his nomadic lifestyle, making him one of the more interesting people to talk about “forced reality” and its effect on travel. Sanja Kojić Mladenov was curator of this exhibition.

DD: How has “forced reality” affected your particular lifestyle and artwork?

DV: I did my best to stay mentally stable and, since I travel a lot, I had to find ways not to let the pandemic completely tie me down. Keeping on the move is very important to me as I can’t create if I stay in one spot.

DD: What impact has travelling had on your view of art and identity?

DV: Ever since I was young, I’ve kept my identity separate from things like nation, flag and country and so moving around has been essential. My art story began in a crisis and since then, creating in one is something that motivates me, not something that makes it more difficult. I think crisis is something an artist needs, when the focus is on ethics and morals; creating in peacetime means you just focus on the aesthetics.

DD: Since your work is often connected to the fall of Yugoslavia and the wars of the 90s, how do you think “forced reality” affects the collective memory of life at that time?

DV: All the former Yugoslav countries tend to ignore that period. They attach a negative context to it, which helps them avoid reflection and analysis. This year will be 30 years since the collapse, but nobody marks the anniversary. As an artist, it bothers me a lot and I can’t ignore it because those events shaped me and my work. What those events did to people can only be seen on the individual level, at the collective level all we see is ignorance and denial.

DD: Can you compare your previous work for the Danube dialogues with this one?

DV: For me there are two worlds: reality and art. Reality is my personal biography, something I went through in life, like the thousands of others who went through the same thing. Art is the world where I feel free to create, and where my role models come in. The core of my work is an exact mixture of those two worlds. The second time I came to the Danube dialogues, I put on a performance based on the fall of Yugoslavia, and the thing I remember most was the emotional reaction from the audience. This year’s performance is much more subtle but still carries an active message. Even though the message this time is from the 1970s, it is still powerful and meaningful in today’s world. It targets the individual, alone in a world where human lives are nothing but a number in statistics.

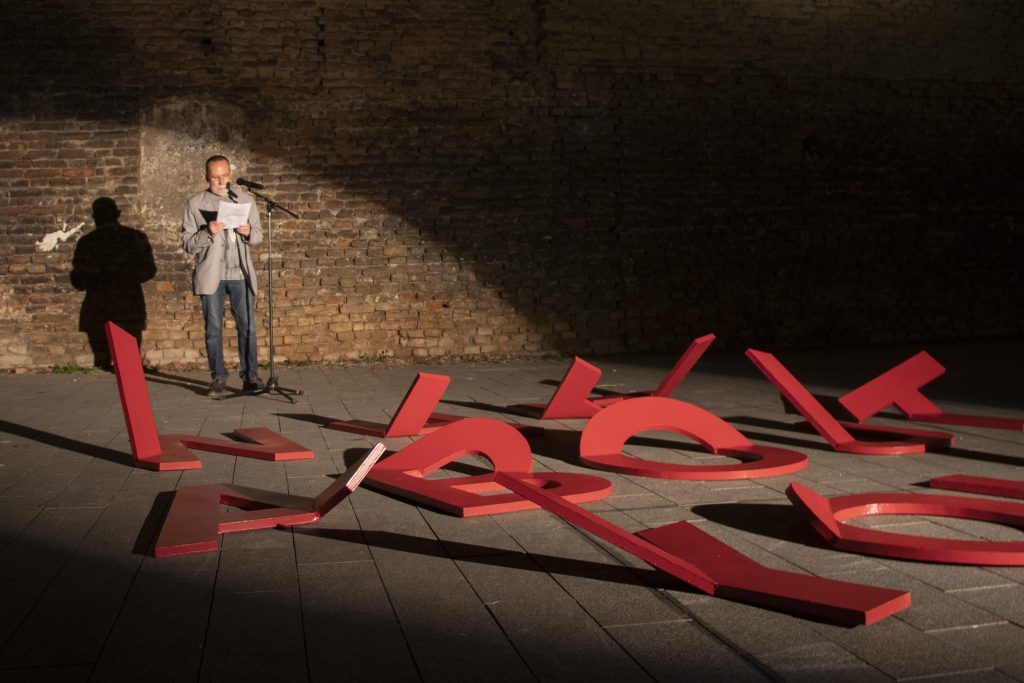

VLADIMIR KOPICL is a Serbian poet, essayist, theatre and literary critic. In a speech at this year’s opening of the Danube dialogues, he not only tackled the problems visited on society by “forced reality” but also offered insight and possible relief to neutralise its effects on the human soul.

DD: How important is the size of the response by artists to the festival and how does it show the quality of these artists and the art scene in general?

VK: While I think it is greatly important, the real question is how many are selected and who is invited. That’s what shows the attitude of the milieu towards art. Artists themselves are very open-minded people. They like to share their work with others and see what their colleagues have to show. This kind of festival symbolizes the vitality of the art scene of the countries in which they are held.

DD: Are festivals like the Danube Dialogues important for the development of the art scene?

VK: Serbia is a festival-prone country that likes to make things happen in vivo. The Danube Dialogues, however, are a cut above the traditional festival “happening”, not only because of the way they’re structured but also because of the dialogue aspect. But entertainment-type festivals are worth having too, as the word itself comes from fest, which suggests a feast, something to look forward to. So we shouldn’t put a full stop between the Exit [pop music], Guča [brass band] and Danube Dialogues [art] festivals – we should put a colon. They’re two clauses of the same sentence we call culture, and everyone should be free to decide which one they like more.