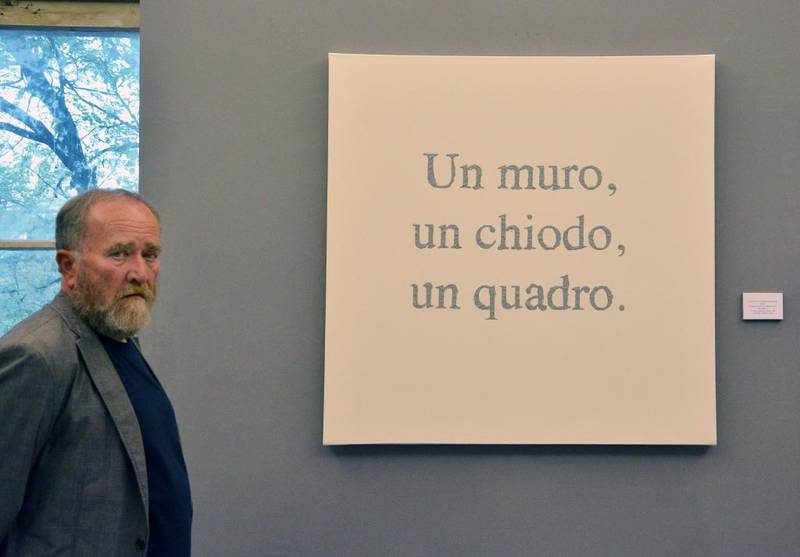

Photo: Courtesy of Curator

Our guest on the latest edition of the Danube Dialogues Bulletin has been a friend of the Festival for many years. Mladen Lučić is an art critic and curator from Croatia and consultant with the Istria Museum of Contemporary Art (MSUI), Pula.

DD: Mr. Lučić, how do you find the whole idea of the Festival and the way it’s developing? Where do you think it succeeds and where do you think it could do better?

ML: I’ve been following and taking part in the Festival from the very beginning and I think that geographically, the default location (contemporary art of the macro Danube region) hits the mark exceptionally well, as it brings together the countries of Central Europe and the Balkan part of the Danube Basin. The macro region is defined in the name, because it includes countries not linked along the Danube, like Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina or Montenegro. However, these are the countries that created the shared art scene of the former Yugoslavia, so it’s only logical that they should be present at a gathering of this kind, which should be seen as a meeting place of Central European and Balkan aspirations in modern art. What we have been seeing for years at the Danube Dialogues clearly says that there are no major differences between us, that distinct national arts are a thing of the past, and that the artists of all countries present here breathe the same air. Where they differ is on the art market, the sale of their work. In Central Europe this functions in line with long-established rules and principles, whereas in the countries of the former Yugoslavia and the Western Balkans – it doesn’t. I assume one of the motives for holding this festival might be to use the exhibition itself and the spin-offs (symposiums, round tables, lectures, projections etc.) to point out the necessity of forming a market and to change the behaviour of galleries and museums across the region east of Vienna. Unfortunately, the Danube Dialogues have not managed to do this – I think it is the only segment in which they’ve failed. It is certainly not the fault of the organisers, but the inertness of a system that simply does not follow up on this event in an adequate way. The Danube Dialogues is not the only case in point, all other countries classed as Balkan are in the same boat, as I personally discovered after three experiences having working on “Here We Are”, a biennial international exhibition of visual arts in Pula, organised by the Istria Museum of Contemporary Art. In the end, I had to give up, despite the fact that they were very successful. It was simply that all we got from public political organisations was promises, with no financial or even moral support whatsoever.

The themes of the Danube Dialogues are up-to-date and follow international trends. The participants (artists, curators, critics) are eminent names in the countries involved, which so far have not kept their creative light under a bushel. On the contrary, when you look at the publications, accompanying information and marketing, you can only conclude that the Danube Dialogues keep pace with similar events throughout the world, and that the agenda and its accomplishment is at the highest possible level for an event of its kind. When we see all the machinery available to the West for various triennials and biennials, and knowing the very small number of people behind the programme and technical demands of the Danube Dialogues, we can only bow down to the floor to all those involved in organising them.

It is a great pity that the Danube Dialogues are not recognised by the institutions, not only of Vojvodina and Serbia but of the region, even in a minimal way, because then they could offer so much more and become an important factor on the international map of similar events. However, the public political organisations think that our Balkan charm and unflagging enthusiasm are enough, never appearing to understand that there is no tangible profit from this. It is why artists from the Balkan countries don’t share in cutting up the European art cake, and why exhibitions by our artists in Western Europe are still the exception rather than the rule of equal participation in the global village. If we do not help ourselves, then international events aren’t of much use even when at the very high level provided for years now by enthusiasts in Novi Sad. And really, in the year 2021, the word “enthusiasm” in this context should be banned once and for all.

DD: Why are regional initiatives, cooperation and agendas like the Danube Dialogues important?

ML: I think I’ve already partially answered this question. I think they’re very important, especially for our part of the world. Economically and artistically, the countries of the Western Balkans depend on one another. The ‘nineties saw the fall of the Eastern Bloc, and the West with the „executive producer“ George Soros immediately coined the phrase Art of Countries in Transit. This was a deliberate cuckoo’s egg intended to keep the art of these countries in their own kind of ghetto by cutingt off access to international markets, which following the economic crisis of 2007, crumbled significantly in any case. Exhibitions such as Manifeste were then an experimental exercise in the production of these countries where a few individuals were recruited into the Western system as a smoke screen, while essentially successfully practising activism – a term politically superimposed on the artistic and an indicator for suppressing individual authorship and artistic thinking, not only in the East, but with increasing frequency in the West. If the experiment didn’t succeed, then artists from the eastern countries were to blame, along with the absolutist regimes from which they came. So it was better to leave the artistic East in its incubator, extracting someone with a tweezers from time to time. The Danube Dialogues recognised this ploy and did not insist on activism, preferring to represent the pluralism of the artistic scene, demonstrating that there were no differences in ethical and esthetic postulates, in conceiving, creating and producing works of art in Germany or in Serbia. This is why insisting on a comparative approach, exchange of experiences and personal encounters yielded a series of positive results, but their further development and inter-collaboration depends not on the Danube Dialogues but on the personal and institutional exchange of participants.

DD: How do you see the theme of this year’s Festival: “Society and Art in a Forced Normality”?

ML: As a theme it’s llogical and not at all surprising. The pandemic has put a brake on the art scene, though to a lesser degree than music or theatre. Most international exhibitions, challenging or studious, have been put on the long finger and whether they will take place at all or not is a big question. A great deal of money has been lost, and many projects have not come to fruition, while some panels and symposiums are being held virtually. The customary contacts and exhibition openings are missing, but thanks to the Internet, there has been sufficient information. However, the Internet is one thing, exhibitions and personal contact quite another. The question that arises here is benefit on the one hand and the dangers of digital communication and social networks on the other. In the past year and a couple of months I took part in several virtual sessions and this novel experience tells me that they come nowhere near the quality of live discussion or of the systematic review of the material supplied on which decisions are taken. I can’t keep up a concentrated and worthwhile participation for long in these discussions (nor can others, I noticed), because it is not in human nature to communicate with a screen, but with another human. In this state of affairs, it’s the social netowrks that profit, as they only communicate in this way where the medium they use detracts from the authenticity, sincerity and credibility of the problem at hand. It narrows the range of perception and flexibility of thinking, which leads to entropy of the critical faculties. However, even before the pandemic, the social networks, mainly because of the speed at which information is exchanged, managed to leave their stamp on the world of visual arts, so that here too there was a decline in quality and critical attitude. It is impossible nowadays to keep up with the speed of information, let alone form a critical opinion of works being sold in this way. I think that due to the force of circumstance imposed by the pandemic, this year’s Danube Dialogues should raise the question of real versus virtual art from the point of view of its presentation, sale and critical thought, and argue for new attitudes in an artistic reality that has been accelerated and accentuated by forced normality.