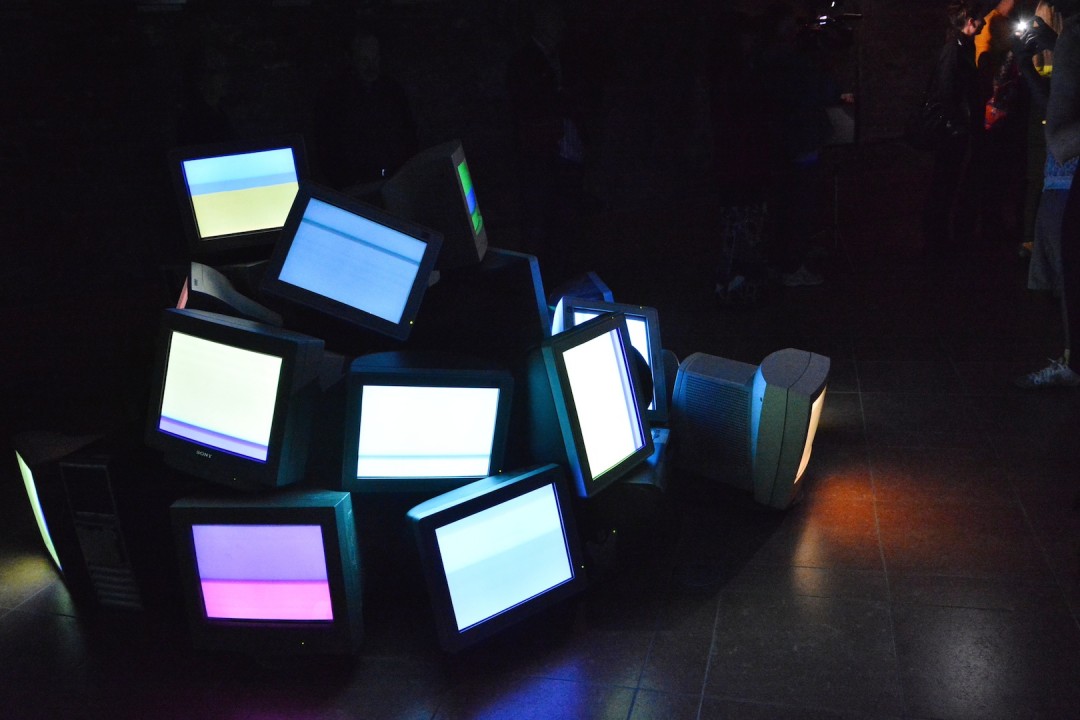

Lokacija: Galerija Podrum (Trg slobode 3)

Curator: Dragan Prole

It has long been recognized that one of the social functions of contemporary art is to introduce new codes of perception. This has made of the artist a kind of trainer in perceptual skills. Like all trainers, it has become the artists’ duty to take their personal exercises a step further than those of the trainees. Their works are thus programmed to integrate the task of going beyond existing perceptual practices – the formulaic association of certain forms and subjects. In pursuit of this, the artwork has mediated the experience of compressing plurality for us. As novel codes of observation necessarily imply an out-of-the-ordinary composition of elements which to most minds would seem heterogeneous and disassociated, the vital job of the artist has come to resemble a kind of school of rapprochement. Things that would normally be organised in an artistic way have become more approachable, closer to hand, more at home. In contrast to plural, mutually alien subjects which have yet to be brought together, an artistic reflex shows us the obverse of our world, in which the practice of art has become bound up with media-moderated forms. The work of Vladimir Frelih does not stop at the perceptual abilities of computer technology. Although cumbersome monitors piled one on top of the other are eloquent reminders of how much of our intimate space we are obliged to hand over to machines, their message is not an existential one. The sheer size of the equipment which until yesterday used to take up a sizeable portion of our desks becomes visible only when they are heaped up to form a sculpture, with all the colours of its various parts. Frelih’s uncommon figure suggests that devices have certain peculiarities of their own, traditionally ascribed exclusively to man. Each piece glows in its own colour, pointing out the individual facets of the various appliances. Although we have since exchanged these massive monitors for slimmer, flatter, more elegant screens, Frelih urges us to look back, to cast a glance on this tacit proximity to equipment we appear to have rejected with ease, forever to remain behind, but whose individual embryo rests on our interactions with it. In contrast to Bruno Latour, who insisted that the social resonance of technology consisted above all in creating distances, Frelih’s works set us off in quite another direction. This is why it seems to us that they in his subtext they posit the contemporary closeness of mediation by humans, technology and the media. This impression is borne out in particular by works which explore the computer-generated colours. Complementary shades overlap as white pops up in the background, muting and softening the vibrancies of the colours. What seems to be a light-hearted game actually conceals the ontology of a painting. Frelih’s pictorial logic takes as its starting point that each colour draws its definition from the blankness of white. Too much light prevents us from seeing anything and an overdose of it leaves us in a position no different from darkness. Awareness of the limits of our computer culture is discreetly hinted at by the interaction of defined and undefined, artistic being and non-being. If the artist is someone who knows what his or her actions imply and what the medial character of knowledge means in his or her time, Frelih’s unusual spectrum warns us that the danger of vanishing is at hand precisely when we think that we have mastered all the finesses and expressive capabilities of the media and technical world in which we live. At this point the annihilating whiteness makes its appearance, sucking into itself all worldly certainties and leaving the impression that there is and can be nothing else apart from it. So we find ourselves in the company of that unpleasing fellow-traveller of contemporaneity personified in the awareness of our own disappearance. And here to install it in the realm of the visible are the experiences offered by the works of Vladimir Frelih.