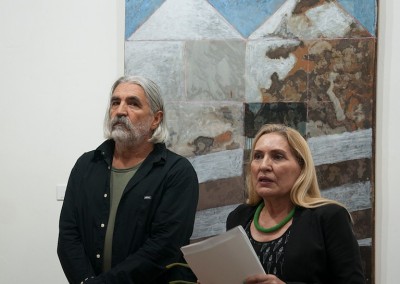

Dan Palade

Curated by Dan Popescu

The Joyous Labour

„This is what old age brings to many labourers: the solid matter they have been dealing with for decades covertly teaches them the eternal aspect of the general fleeting destiny. Under their gaze locomotives have come out of use, have lain for years in the sun, and have then been sent to the scrapyard.“

(Andrei Platonov – Cevengur)

When Communism ended, I was entering adolescence. I remember both the deprivation a Bucharest city-dweller went through in last century‘s late 8th decade, and the solar bliss of a childhood where there was still a schoolyard playground, where truths were experienced, not described on the Internet. I know I was wondering when there would be a West here, for us, what will become of all the seemingly pervasive signs? They promised a bright future, wished the leader health and strength, proposed universal peace, prescribed a solar vocation for the factory worker. Industry was everything, there was honest work going on there, even the signs were welded and constructed through heavy metallurgical processing. Everything seemed incorruptible, slogans were the new iron-welded prayers, workers the new oven-tempered saints, Communism – the new red religion blowing off brimstone, coke and smut. In the two years at the beginning of the 90s, all those eternally ironclad wishes and desires disappeared without a trace. It seemed incredible even for me, having experienced workers‘ Communism more from the sidelines, being too small, having all options open, not having made any decisive choice yet. My soul had lived some years before ’89 but my eyes only opened after the Revolution. Dan Palade was born at the same time as the Communist industry, and was at a Christ like age during the fall of the Iron Curtain. He was born in Onesti, a Moldavian town where girls grow up to be gymnasts and men worked in petrochemistry. His family wants him to study violin, but he is seduced by the scent of turpentine in the painting class next door. Rebelliously he wants to be autonomous and gets employed in the socialist industry. There weren‘t however many options at the time, any liberal life choice was gained through taking risks. He needs to be legal to ‚fuel‘ his personal crimes. Communism promised a layman‘s emancipation, but the way this would be achieved had all the signs of Messianic mysticism. The solar path, the new man, personal emancipation was accomplished through work, and the noblest of work, kosher work, was that which took place in factories. This mystical view of work structured into specialized industries was not just a concept with no charisma. This rhetoric seduced many, spawned a new personal horizon while other soteriological solutions were eyed suspiciously. Dan, however, does not adhere to this myth. He works hard in factories, performs all the toxic jobs petrochemistry entails, but keeps two burning desires in his heart: do painting, and leave the country. He barely manages to fuel the first one outside working hours, but has no luck with the second. Beyond his personal background, Dan is a fine example of non-adherence to the Communist mythology built around work. In the Carpatho-Danubian space, and maybe even in the Balkans, work is not an activity through which the individual reaches salvation. It is seen as a chore, a byproduct of the fall from Heaven. There is a Romanian word of Slavic origin – ‚slujba‘, often used, that strongly reinforces viewing work as a drudge. It‘s very likely that the Communist idealization of the collective working effort was an import from the Western culture – protestant. Thus, only an incomplete hybridization took place in a Romanian fatalistic space. The Romanian excels in irony, mood, and existential doubt more than in obsessing over building a future through sustained labour. Dan Palade is an example for the way this conflict could have been solved. It‘s not about the refusal of work in his case, but instead it‘s a matter of not adhering to the Communist mythology of salvation through industrial labour. On the other hand, Dan was looking for another kind of equilibrium, that of joyous labour. Joyous labour cannot have a fixed schedule, it is not imposed, but done willingly, it rarely produces useful items and it is rather an interior construction than an accumulation of things. It is what we normally encompass within the term ‚art‘. All that comes from artistic effort does not serve ‚the people‘, but instead ails the soul of a worker looking for release from a chore through art. The years of transition to an open society are lived with a mix of hope and bitter disgust. The world disappoints and then the inner artistic struggle gains even more pull. Dan‘s works become melancholic snapshots of a world who would produce iron and concrete colossi that have now sunken into the ground, into forgetfulness, into nothingness. The stake of works with toxic titles such as ‚Chlorine cloud‘, ‚Solvent‘, ‚Cyanide fog‘, or ‚Withdrawal‘ pertains to denying the void of forgetting, of the possible disappearance of what used to be imagination, the ideal of construction through joyous labour. The industrial juggernauts have fallen, rusted and gone into the ground, the goats graze peacefully among the barely noticeable ruins. Only the memory persists in the soul of the artist, like an undefeatable spectre.

The further away I got from the experience and trauma of Socialist construction years, the more present and syncretic would become the shapes of industrial buildings – huge warehouses, reservoirs and decantation and refinery pillars, furnaces and cooling towers, trestles and serpentines – bridges from the past to my present, chased by morning cyanide fogs of a rebellious proletarian. Images I would synthesize in the present context as corrosive attacks on the organic background of the horizon, a transfer on the gelatine of the transcendent, a mutual contradiction between form and sign. This is how these images were born, shadowed by the hint of reality bearing the spirit of olden days‘ form. If the soul moves the body, then mind expresses form!‘ (Dan Palade).

29 AVG – 12 SEP

The Gallery of Fine Arts – Gift Collection of Rajko Mamuzić, Novi Sad, Vase stajića 1